The business of filling stomachs is lucrative. The ten most valuable packaged food and soft drink companies in the West have a combined market capitalisation of around $1 trillion. Their average operating margin last year was a generous 17%; supermarkets typically get only 2-4%. Consumers have continued to enjoy the cheap calories offered by these companies despite the recent bout of inflation. Last year, the group’s sales grew by 5%, on average. Rising demand in the developing world is driving growth. About half of Coca-Cola’s revenues already come from markets outside the West. HSBC bank estimates that global food demand will rise by more than 40% between now and 2040.

But the industry also faces threats. The impact of its products on the health of those who consume them has long been a concern for both buyers and policymakers. Now consumers may consume less of them, as slimming drugs become cheaper and more convenient. What’s more, a growing body of research suggests that it’s not just the excess sugar, fat and salt that can cause health problems, but also the heavy processing used to prepare cheap snacks. Both are set to reshape the industry and transform what the world eats.

The roots of today’s food industry go back to 19th-century innovations like pasteurization and canning, which helped make food plentiful, convenient and safe. Today, a humble bag of chips is made on an assembly line where potatoes are sliced, fried, soaked in seasonings, preservatives and coloring, then sealed in a nitrogen-filled bag to prevent them from going stale. The process takes about 30 minutes.

These tasty products have contributed to the rise in obesity in recent decades. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the average daily caloric intake of people in rich countries has increased by a fifth since the 1960s, to 3,500 calories – far above their bodies’ needs. It is estimated that by the end of this decade, almost half of the world’s population will be obese or overweight.

Consumers who have previously found it difficult to change their diets can finally do so, thanks to blockbuster new weight-loss drugs such as Wegovy (from Novo Nordisk, a Danish pharmaceutical company) and Zepbound (from Eli Lilly, a US rival). For now, the high price and inconvenience of weekly injections mean that only a small fraction of people in rich countries take these drugs, but their use is expected to increase as competition drives down prices and pill forms come onto the market.

Patients taking these drugs have reported fewer cravings for high-calorie foods. An analysis by the research firm Grocery Doppio found that users cut their grocery spending by an average of 11%, with spending on snacks and candy falling by more than half. Morgan Stanley, a bank, estimates that 7% to 9% of Americans could be taking weight-loss drugs by 2035, resulting in reductions in overall demand ranging from 3% for cereal to 5% for ice cream (see chart 1).

View full image

Big food companies may take these developments in stride. The industry has a history of launching new products that meet the needs of weight-conscious consumers. Coca-Cola first launched Diet Coke in 1982 and has since launched several other sugar-free alternatives. Most food and beverage companies now offer products with less sugar, fat or salt. According to Mintel, a market research firm, the number of new healthy snacks launched annually rose 2% between 2015 and 2020, compared with a 1% decline for traditional snacks. Some companies, such as Mondelez, a US snack giant, now offer smaller portions.

In fact, several food companies see weight-loss drugs as an opportunity. In May, Nestlé, the world’s largest such company, said it would launch a new frozen food brand, Vital Pursuit, aimed at users of the drugs, who still need to make sure they get adequate amounts of protein and other nutrients despite consuming smaller amounts of food. Mark Schneider, the company’s chief executive, says Nestlé is already preparing for a “lower-calorie, higher-nutrient future.” Last year, the company set a goal of increasing sales of “more nutritious” products by 50 percent by the end of the decade. Other packaged-food companies, such as Conagra and General Mills, also now have products aimed at users of weight-loss injections.

New businesses may try to steal their lunch, but established ones will be in a strong position to serve consumers looking for nutritious, low-calorie options. It takes only six to nine months to develop and launch a new product, Schneider says. Close ties with supermarkets and other retailers make it easier to get products on shelves once they are ready. Large marketing budgets can be devoted to raising consumer awareness.

Food for thought

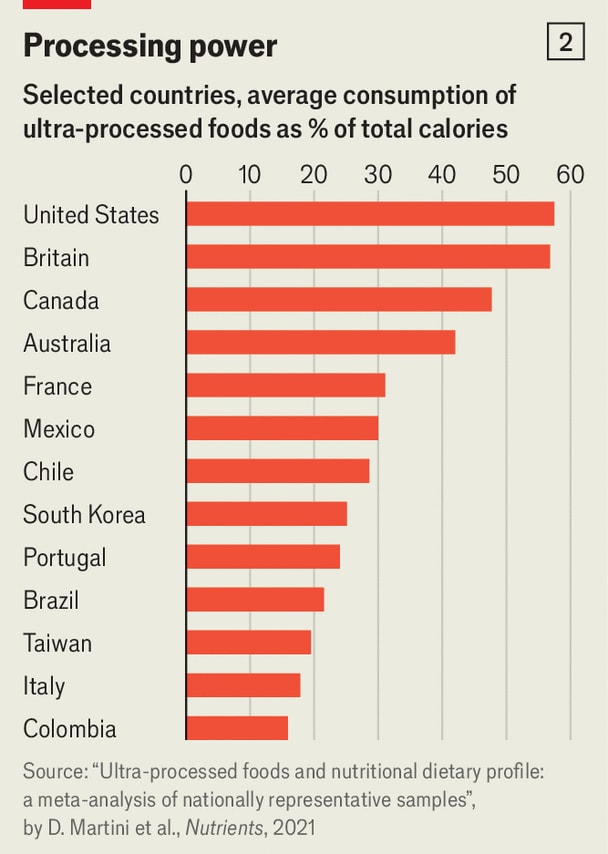

The threat of a crackdown on processed foods, if it materialises, will be harder to deal with. In 2009, Carlos Monteiro, a Brazilian scientist, classified foods into four categories based on the degree of processing they have undergone. The first covers unprocessed products such as fruit and vegetables. The last, called ultra-processed foods (UPF), covers products such as breakfast cereals, frozen pizza, chips and soft drinks, which contain significant amounts of ingredients not typically found in a home kitchen. Since the 1990s, the proportion of UPF in diets around the world has been increasing. According to one study, they now account for around half of calorie intake in the United States, Britain and Canada (see chart 2). Many studies have linked the consumption of large amounts of UPF to weight gain and various health problems, although some do not separate the effects of excessive processing from the large doses of fat, sugar and salt typically found in these foods.

View full image

The research is in its infancy and not everyone is convinced. Arne Astrup, a researcher at the Novo Nordisk Foundation in Denmark, believes the definition of UPF is too vague. But policymakers in some countries are already taking action. In November last year, Colombia imposed a tax on a range of UPFs. Dietary guidelines in Belgium, Brazil, Canada and other countries recommend avoiding these products. Monteiro has called for labelling the health hazards on UPFs, as many countries have done with cigarettes.

So far, the industry’s attitude toward UPFs has ranged from skepticism to lack of judgment. Ramon Laguarta, PepsiCo’s chief executive, said in January that he doesn’t believe in the term; Schneider says Nestlé is watching the debate “very closely.” But the stakes are high. If government pressure mounts, then the industry will have to do more than just tweak its recipes or launch a new product line. Companies would have to overhaul their manufacturing processes. Removing additives could make products more expensive to make and shorten their shelf life, cutting into profits. So far, big food companies have managed to thrive even as concerns about consumer health arose. With UPFs, it could face its most daunting challenge yet.

© 2024, The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. From The Economist, published under license. The original content can be found at www.economist.com

Disclaimer:

The information contained in this post is for general information purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the post for any purpose.

We respect the intellectual property rights of content creators. If you are the owner of any material featured on our website and have concerns about its use, please contact us. We are committed to addressing any copyright issues promptly and will remove any material within 2 days of receiving a request from the rightful owner.