By Akshat Rathi and Natasha White

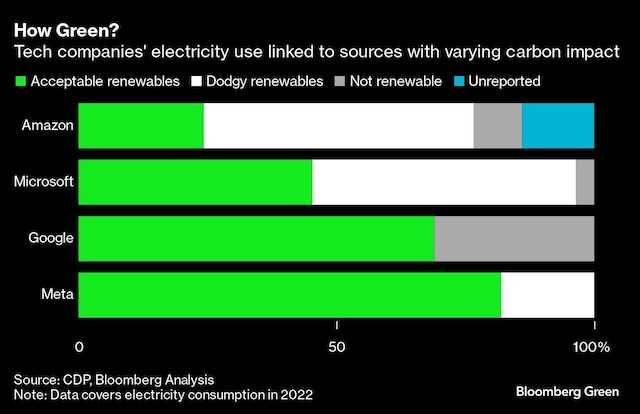

Tech companies’ relentless push into artificial intelligence comes at an undisclosed cost to the planet. Amazon, Microsoft and Meta are hiding their true carbon footprints and buying credits tied to electricity use that improperly erase millions of tons of planet-warming emissions from their carbon accounts, according to a Bloomberg Green analysis.

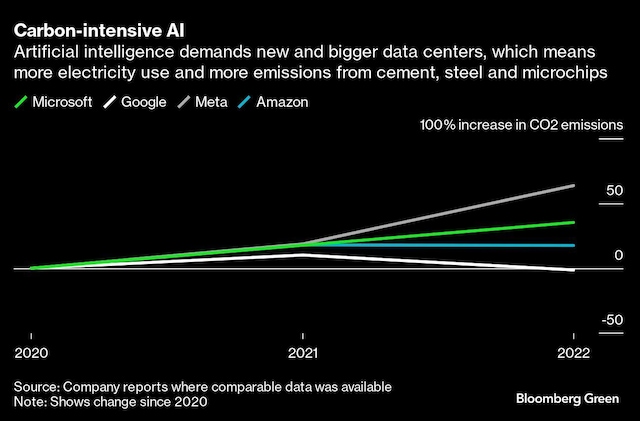

Microsoft recently reported that its emissions are 30% higher today than they were in 2020, when it set a goal to become carbon negative. Emissions from other tech companies are also rising. However, Microsoft and other AI leaders insist the increase is due to the high-carbon materials used to build data centers — cement, steel, and microchips — and not the massive amount of energy AI requires. That’s because they have said the energy comes mostly or entirely from zero-carbon sources, such as solar and wind.

Is AI powered exclusively by clean energy? “There is no physical reality to support that claim,” said Michael Gillenwater, executive director of the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute.

Companies are buying credits, called unbundled renewable energy certificates (RECs), that can make it appear that energy consumed at a coal plant came from a solar farm. Amazon, Microsoft and Meta rely on millions of unbundled RECs each year to claim emissions reductions when they make voluntary disclosures to CDP, a nonprofit that runs a global environmental reporting system.

Current carbon accounting rules allow the use of these credits to calculate a company’s carbon footprint. However, work by many academics shows that accounting rules need to be updated to accurately reflect greenhouse gas emissions.

That’s because these carbon savings on paper are not actual reductions in emissions in the atmosphere. If companies did not account for disaggregated RECs, Amazon could be forced to admit that its 2022 emissions are 8.5 million metric tons of CO2 higher than reported — three times what the company disclosed and matching Mozambique’s annual impact. Microsoft’s sum could be 3.3 million tons higher than its reported count of 288,000 tons. And Meta’s reported footprint could increase by 740,000 tons from near zero. (See below for methodological details.)

“Companies should not be allowed to use disaggregated RECs to claim they have reduced their emissions,” said Silke Mooldijk, who focuses on corporate climate responsibility at the nonprofit NewClimate Institute. “It is misleading for consumers and investors.”

Not all tech companies have gobbled up disaggregated RECs to hide the rising emissions that have resulted from the tight AI race. Alphabet Inc.’s Google phased out its use of disaggregated RECs several years ago after acknowledging that they do not equate to real emissions reductions. “Studies have raised legitimate questions about whether [these credits] “Renewable energy can replace fossil fuel-based power generation,” said Michael Terrell, senior director of energy and climate at Google.

Amazon relied on unbundled RECs for 52% of its renewable energy in 2022, making it the most dependent of the four instruments. An Amazon spokesperson said the amount of unbundled RECs the company uses is expected to “decline over time” as more directly contracted renewable energy projects come online. Microsoft, which relied on unbundled RECs for 51% of its renewable energy, also plans to “phase out the use of unbundled RECs over the next few years,” a company spokesperson said.

A spokesperson for Meta, which relied on unbundled RECs and utility-labeled “green” power for 18% of its renewable energy, said the company takes “a thoughtful approach” and that “the majority” of the company’s “renewable energy efforts” are focused on projects that “would not otherwise have been built.”

The thousands of companies using Amazon-powered AI for their customer chatbots, Microsoft’s AI Copilot for summarizing meetings, or Meta’s Llama for generating images may assume there are little to no energy emissions by relying on these models. It’s a powerful marketing tool for these big tech companies, helping to allay the concerns of potential customers who are likely to feel pressure from users and investors to reduce their own carbon footprint. In reality, it’s creating a cascading impact of misinformed emissions and increasing demand for energy-hungry AI products.

“If consumers don’t understand what the climate impact of AI is, because tech companies don’t report on it transparently, then there is no incentive for consumers to change their behaviour and adopt a different AI model,” Mooldijk said.

It’s also a problem in the financial realm. Banks and investors who tend to include big tech in sustainable funds too often accept emissions claims at face value. “At the moment, there is simply no sophisticated understanding of this issue,” said Gerard Pieters, director of Tierra Underwriting, which helps banks on clean energy deals. “We’re still in a period where people make claims quite easily and they are simply copied and accepted as fact.”

Technology companies are the largest buyers of disaggregated RECs in the world. Whether or not they continue to buy these credits to make claims about their climate impact is very important, as more and more corporations look to reduce their carbon footprint and green their credentials.

To understand how RECs work for businesses, you have to consider where the energy generated on a grid comes from. Typically, it comes from a mix of sources – from coal and gas to wind and solar. Climate-conscious businesses are increasingly looking to source energy exclusively from sources that generate the fewest emissions that contribute to global warming.

One way to do this is to sign a clean energy contract directly with the supplier through a power purchase agreement, where the tech company signs a long-term contract and thus takes on some of the risk over a 10- or 15-year period. That, in turn, makes it easier for the developer to get the financing to build the solar or wind farm.

To help tech companies track the source of that energy, renewable energy producers also issue energy attribute certificates, or RECs, which are a type of tracking tool. However, RECs can also be purchased on their own, separately from the purchase of electricity. The idea behind these so-called “unbundled” RECs is that there is value in renewable energy generation beyond the electrons produced and sold: the lack of emissions also has a value. So since renewable energy generators produce two things of value (energy, and specifically, low-emissions energy), they should be able to get paid not only for producing electricity, but also for being green.

This idea—and the calculation that came from it—was developed when renewable energy was expensive to produce and could not compete on price with fossil fuels. The idea was that the extra money renewable energy developers would receive in the form of RECs could act as an incentive to produce more wind and solar power than would otherwise have been done, and thus be “additional.”

Studies in 2010 showed that unbundled RECs weren’t living up to that theory of stimulating renewable energy production. But that inconvenient fact was mostly ignored, and the enthusiasm for RECs led to a quirk in emissions reporting rules that allows companies to buy unbundled RECs and then deduct the emissions from their CO2 accounts. This means that companies can report reduced emissions from their electricity consumption even if their actual consumption hasn’t changed in any way (and may still come from a coal-fired power plant).

Solar and wind power have become cheaper than the fossil fuel alternative, and there is growing evidence that most disaggregated RECs are not what emissions counters call “additional.” That is, they do not stimulate the construction of new wind or solar farms, and so there is no second value for which producers must be paid, and certainly no emissions reduction for the buyer.

“The widespread use of RECs… allows companies to report emissions reductions that are not real,” Anders Bjorn, an adjunct professor at the Technical University of Denmark, and a team of researchers wrote in a paper published in the journal Nature in June 2022. After adjusting for companies’ use of RECs, they found that 40% no longer showed alignment of their activities with the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global warming below 1.5°C.

Last month, Amazon claimed it had reached 100% renewable energy use by 2023 using its own accounting methodology and will therefore have zero emissions from electricity use. The company has not yet reported details supporting its renewable energy consumption in 2023, but Bloomberg Green analysis suggests the claim is likely based on the use of disaggregated RECs. In response, an Amazon spokesperson said: “It can take several years for projects we invest in to come online, so we sometimes use disaggregated RECs — a critical part of the global renewable energy market — to temporarily fill the gap until a project’s operational date.”

Like Amazon, Google claims to use 100% renewable energy globally. Rather than using disaggregated RECs, Google purchases more clean energy than it consumes in some places, such as Europe, and less in others, such as Asia-Pacific, depending on availability in those places. Google, however, makes clear that it does not consume carbon-free energy on an hourly, location-specific basis. That is now “our ultimate goal,” Terrell said.

Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and Google are all following accounting rules laid out in the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which was first developed in 2001. Those disclosures underpin the analyses that investors rely on to make decisions about what is considered a green company. While the protocol has received minor updates over the years, a major update is expected, and experts are working to propose changes. All of the big tech companies are now involved in lobbying for those changes.

“Standards need to evolve because measuring carbon emissions is not an exact science,” said Google’s Terrell. “It continues to improve and we are committed to helping improve it.”

Disclaimer:

The information contained in this post is for general information purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the post for any purpose.

We respect the intellectual property rights of content creators. If you are the owner of any material featured on our website and have concerns about its use, please contact us. We are committed to addressing any copyright issues promptly and will remove any material within 2 days of receiving a request from the rightful owner.