Traditionally, grid-scale storage relied on hydroelectric systems that moved water between reservoirs at the top and bottom of a slope. Today, giant batteries stacked in rows of sheds are increasingly the method of choice. According to the IEA, 90 GW of battery storage was installed globally last year, double the amount in 2022, with about two-thirds going to the grid and the rest to other applications such as residential solar. Prices are coming down and new chemistries are being developed. Consultancy Bain estimates the grid-scale storage market could expand from about $15 billion in 2023 to between $200 billion and $700 billion in 2030, and $1 trillion to $3 trillion in 2040.

View full image

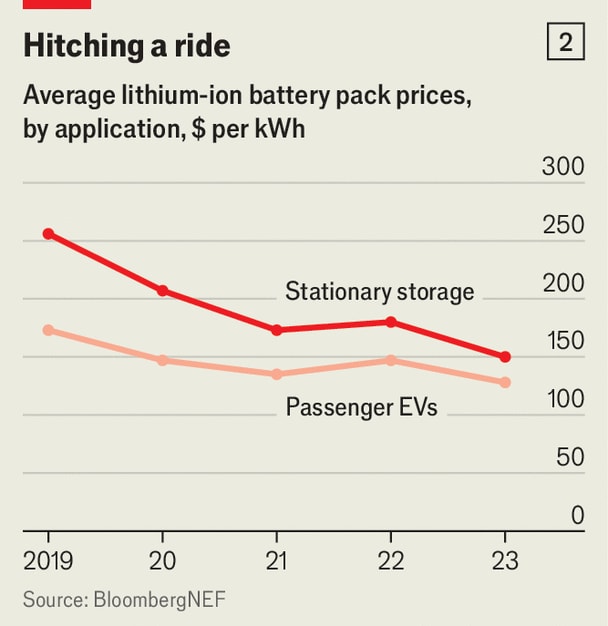

Falling lithium battery prices are driving their adoption on the grid. According to BloombergNEF, a research group, the average price of stationary lithium batteries per kilowatt-hour of storage fell by about 40% between 2019 and 2023. A global slowdown in the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), which run on similar technology, has led battery makers to take a greater interest in grid storage. In 2019, stationary lithium batteries were nearly 50% more expensive than those used in EVs; that gap has narrowed to less than 20% as producers have come on board (see chart 2). The IEA finds that solar combined with batteries is now competitive with coal-fired power in India, and on track to be cheaper than gas-fired power in the United States within a few years.

View full image

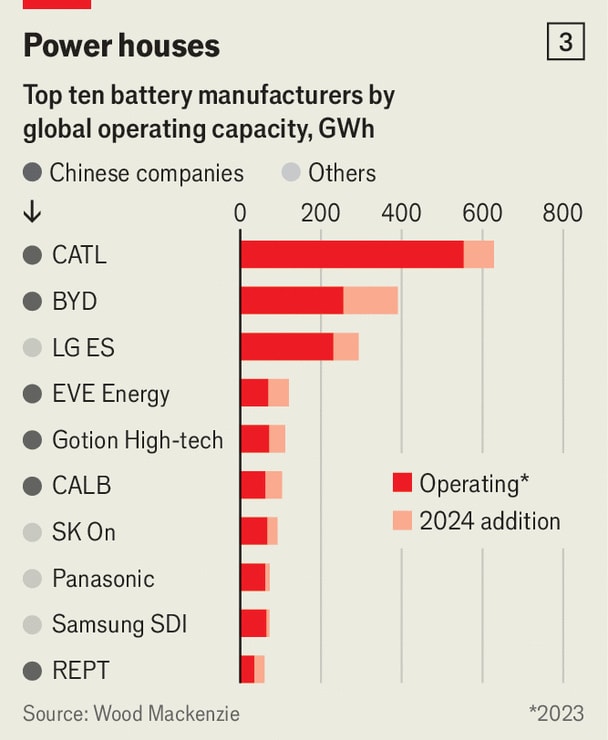

The centre of global battery production is China, home to six of the world’s ten largest manufacturers, including CATL and BYD (see chart 3). The share of China’s battery production destined for power grids has risen from almost nothing in 2020 to around a fifth last year, surpassing the share used in consumer electronics. Growth has been helped by domestic policies mandating that large solar and wind projects also install storage systems.

View full image

Chinese battery companies are intensely innovative. CATL has increased its research and development spending eightfold since 2018, to $2.5 billion last year. BYD, which has invested heavily in robotics and artificial intelligence, has built a battery plant in the city of Hefei that is almost entirely automated. But the industry is also swimming in excess capacity. According to BloombergNEF, China alone already produces enough lithium batteries to meet global demand of all kinds. Its industry has announced plans for an additional 5.8 terawatt-hours (TWh) of capacity by 2025, more than double the current global capacity of 2.6 TWh.

This will be catastrophic for many companies in the battery industry, including those producing for the power grid. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, another research study, the construction of 19 battery gigafactories in China was cancelled or postponed in the first seven months of 2024. The price crash has also hit many Western battery startups. One example is Sweden’s Northvolt, seen by some as Europe’s answer to China’s champions. Last year it reported a loss of $1.2 billion, compared with $285 million in 2022. The consequence is likely to be a wave of consolidation, as Robin Zeng, CATL’s chief executive, predicted earlier this year.

Still, a bloodbath among battery makers could help, rather than hurt, the adoption of battery storage. Prices could fall further as more productive companies grab a larger share of the market. Fierce competition is already spurring innovation as companies seek new technologies to help them compete. Sodium-ion batteries are a promising alternative. They don’t require expensive lithium, and while they offer lower energy density, that’s less of a problem for stationary batteries than for those powering electric vehicles.

Traditional companies are racing to develop the technology for the power grid, and several startups are betting big on it, too. Natron, a U.S. company backed by Chevron, an oil giant, is investing $1.4 billion to build a sodium-ion battery factory in North Carolina, scheduled to open in 2027. Landon Mossburg, chief executive of Peak Energy, another sodium-ion startup, says he wants his company to be “America’s CATL.”

Tom Jensen, the head of Freyr Battery, another startup, believes the only way Western battery companies will be able to compete is with new technologies. The list of innovative approaches is growing. EnerVenue, another startup, is commercializing a nickel-hydrogen battery. The firm has raised more than $400 million and will build a plant in Kentucky that it hopes will produce cheap batteries that can store energy for long periods.

The fact that these new technologies are well-suited to meeting the growing power demand of data centers, which tech giants are eager to run on renewable energy, helps. The fact that sodium-ion batteries are less likely to catch fire than lithium batteries makes them particularly attractive to tech companies, not least because it reduces the cost of insurance, notes Jeff Chamberlain, the head of Volta Energy Technologies, an investment firm focused on energy storage. Colin Wessels, co-director of Natron, notes that his startup plans to supply batteries primarily to data centers.

The rapid deployment of data centers is also creating gaps in the infrastructure used to generate and transmit power that could be filled by longer-lasting batteries, such as those EnerVenue hopes to produce. Aaron Zubaty, chief executive of Eolian, a renewable energy developer, predicts a boom in four- to eight-hour storage solutions to meet rising demand on power grids over the next decade.

Grid-scale storage is advancing rapidly. “Batteries have done in five years what it took solar fifteen,” says one veteran analyst of the solar boom, who now covers the sector. As Fatih Birol, director of the IEA, sums up: “Batteries are changing the rules of the game before our eyes.”

© 2024, The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. From The Economist, published under license. The original content can be found at www.economist.com

Disclaimer:

The information contained in this post is for general information purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the post for any purpose.

We respect the intellectual property rights of content creators. If you are the owner of any material featured on our website and have concerns about its use, please contact us. We are committed to addressing any copyright issues promptly and will remove any material within 2 days of receiving a request from the rightful owner.